|

|

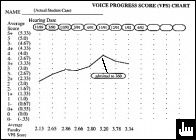

Keeping Track 1 When I first came to BYU as Director of Opera in 1973, my teaching load was split between opera directing and choral conducting. I chose not to teach private voice because I saw a potential conflict of interest in casting my own students in operas. I risked unfairly overlooking my own students for political reasons as well as unfairly favoring them because they were mine. But there came a time in the early 1980's when two needs converged in me. My experiences with choruses and with group voice had awaked in me a passion to figure out what really caused vocal beauty. This desire joined my need to get the most beautiful singing possible from the students I had cast in the opera productions. I negotiated my teaching load so that I could teach some lower division voice majors. This was during my impatience phase mentioned at the beginning of chapter 6. I told my students glibly, "If you haven't learned to sing really beautifully within two years I will insist that you move on to another teacher." My colleagues smiled and jokingly referred to me as "Mr. Insta-voice." I soon became wiser. It was indeed going to take us longer than I had thought to figure out this beautiful singing thing. I also soon got frustrated seeing my singers move on to other studios before I was satisfied with their singing. But if I taught more advanced students, how I would resolve the conflict of interest as I cast the operas? VOICE PROGRESS SCORING Out of this dilemma arose an illuminating moment of reasonable thinking. My colleagues agreed to attend the opera auditions and score our students' performances there. I then tried to choose operas that would feature the students who received the highest average scores. I reserved enough flexibility to assure the right vocal timbre, personality, and sufficient acting capacity in the leading roles, and I always circulated the proposed casting for faculty approval before posting it. The faculty appreciated being included in those important decisions. To make our scoring as objective as possible, we eventually agreed upon a benchmark description for each score level. These came to be called Voice Progress Scores (VPS): VPS SCORE With the option to add + or - to any of the above scores, we had a relatively objective scale of eighteen segments or, using decimal points, a continuous scale. In order to protect the scoring from undue influence by a faculty member who might be strongly biased either for or against a student, a faculty score which fell farther than one semi-score away from its next nearest neighbor would be adjusted back to the neighboring semi-score. Thus the low or high score would still have modest weight but could not distort the whole

It didn't take us long to see that there were many advantages to recording these scores, and we started scoring all hearings, including semester-end proficiencies, recital hearings, advancement hearings, and entrance auditions. We posted these averaged and adjusted VPS scores on a graph kept in each student's departmental file (see figure 8.1). VIDEOTAPING EACH STUDENT HEARING As inexpensive video cameras became available, we began to record on each student's personal videotape all of these VPS hearings, starting with the admission audition and continuing through the graduation recital. This is part of the evidentiary path that documents the students' growth and confirms the VPS scores. We store the tape in department files that can be moved into each hearing session along with the video recording equipment. We don't rewind the tape, but always keep it cued to record the next faculty hearing. At graduation, transfer to another school, or change of major, we return the tape to the student as a meaningful memento of his total learning experience. This little bit of extra effort required for the VPS tallying and recording and for the videotaping has helped us in many ways: First, we can immediately and accurately account for exceptional growth (or regression) in the individual student. Recently, the faculty voted to accept a student provisionally into upper division work in a performance/pedagogy major. At the next proficiency, the faculty majority voted to deny continuation. At the conclusion of the day of hearings the student's teacher was puzzled by that vote in light of her own estimate of the student's exceptional growth for the semester. She suggested that before we sent the denial letter, we should post the faculty average score on her VPS chart for comparison with the semester of her admission and then replay the last two hearings from the videotape. The scoring system and video backup kept us honest. The teacher was clearly right. The growth between the two performances was in fact so exceptional that there was no way any of us could justify remitting her to lower division work. We provisionally continued her for another semester with the anticipation that she would be able to maintain at least a part of that stunning growth pattern. In an opposite case, we voted to provisionally admit a student who had struggled for a long time to get into our program. In spite of vigorous and intelligent work in the studio, the student's semester-end proficiency revealed that all of the former glaring inadequacies were still lingering in her voice. The student's frustration was quite easily allayed as she viewed with her teacher the video recordings of several of her proficiency performances in succession. This made it emotionally easier for her to transfer into a major that required less demanding vocal capacities. Second, when students move from class voice into private studios or between studios, we can minimize the slippage in vocal technique. One faculty member was very puzzled when the VPS score for one of her new students showed a significant drop from a prior semester. As she reviewed for the first time the succession of video recordings of the student's proficiency auditions, including the one which had passed the student from Vocal Beauty Boot Camp (see chapter 11) into her private studio, she exclaimed, "Why, she certainly didn't sing that well when she came into my studio in September! If I had known she was that good last spring I would have expected a lot more from her this fall. I can see now why her VPS went down. How did the boot camp instructor help her get her voice that full, clear, secure, and in tune? Why didn't she hold on to it over the summer? Why didn't we get it back during the semester?" Needless to say the teacher began to seek some healthy answers from her colleagues. In a most dramatic case, a young tenor who was finally singing very freely and beautifully in the 4.0 VPS range decided that he should change teachers. The new teacher had not yet discovered the insights that the student's videotaped performance history could yield and assumed that the student was still "muscling his way through his voice," as he had done in earlier semesters. Perhaps because of the summer break he had even reverted to his old muscle style when he first sang for the new teacher in September. She thus spent the year diligently "backing him off again" rather than building on the tremendous progress he had already made. He obediently followed her counsel, but discovered at the next two semester proficiency hearings that the faculty scored him down significantly from his previous year's hearing. Angrily suspecting bias against him by the faculty jurors who had all advised him to stay with the prior teacher, the student made an appointment to complain to the Voice Area Head and then went straight to the Music Department Chairman. Both reminded him that the truth would be found in the careful VPS records and the videotaped history in his file, which he should first consult. With indignation, he checked out his videotape. The next morning he talked to the Vocal Area Head, but with a much changed and more receptive spirit: "Well, you may not believe this, but when I looked at the videotape last night, I honestly had to admit that the jurors were right yesterday. I was singing so beautifully last year that it was even thrilling for me to listen to myself. But the two proficiency performances this year were really quite dull in comparison. Even though I was doing exactly what my new teacher wanted me to do, she didn't realize that I was further along the path. I should have shown her the tape." We find it imperative at the beginning of each term, before setting new objectives, to review with the student the ultimate truth-teller, the videotape, as we read together the written faculty comments on their jury sheets. Third, we can quickly discern and acknowledge studio success patterns. Within a semester after one teacher discovered the importance of getting her students' neck posture "long, back, and free," not only did faculty comments about poor posture virtually disappear from her students' proficiency grading forms, but she was also reinforced in her work with the knowledge that her average student VPS growth for the semester had been +0.49 (on our 0 to 5.33 VPS scale) against a departmental average of only +0.25. There is a confidence that comes from knowing how well we are doing. UNEXPECTED ADVANTAGES In addition to providing a relatively objective measure of progress for the student and teacher, regular use of this scoring system has proved most helpful in a number of unforeseen ways. Fourth, we can see more objectively how we can best help one another improve as teachers. Average VPS improvement over several semesters for all students at a given level in a given studio has helped to identify those teachers who tend to be most successful at various levels of instruction. Some teachers emerge as good "jump starters," able to coax new students quickly into beautiful full-voiced technique. Other teachers seem most successful in polishing and expanding the capacities of intermediate students, while still others seem most able to trigger that theatrical vulnerability which exciting professional performances require. As the composite VPS scorings begin to identify particular teaching strengths, we find it easier to consult with one another for ideas and insights as well as to refer students to one another for focused help on technique, interpretation, or repertoire. Frequently we invite one another into our studios to work jointly with a student on a problem, and we have even worked helpfully with one another's students in combined studio classes. Fifth, we can objectively assess the flat places in our overall vocal program, so it becomes easier to develop an informed plan to change things. For example, after analyzing successive average scores for all voice majors in the school, we saw that we were quite successful at getting young voices quickly on the way to healthy, beautiful, physically integrated vocal technique. They got to where we would enjoy hearing them sing their hour-long senior recital. However, most of our students tended to flatten out in growth once they reached "3+" to "4-" on the VPS scale. Consequently, we made some shifts in curriculum aimed at helping our students find a path across that 4.0 VPS barrier and into exciting, professional quality performances. Footnotes 1 This is a revision of my article "Voice Students of the University II: Managing Student Growth," NATS Journal, (Jan/Feb 1993) 18-21, which I also wrote while still serving as Vocal Area Head in the School of Music at BYU. The following Brigham Young University voice faculty members ratified the article for its original publication: Matthew Bean, Marjo Burdette, Arden Hopkin, Marion Miller, Shirley Westwood, Randy Booth, Marilyn Gneiting, Gayle Lockwood, Barry Bounous, C. Houston Hill, Rosemary Mathews, and Lila Stuart. |